Jordan Smith of The Intercept explains the case of Jeff Wood and the law of parties in her August 2, 2016 article, “Jeff Wood Didn’t Kill Anyone, but Texas is About to Execute Him Anyway”.

Jordan Smith of The Intercept explains the case of Jeff Wood and the law of parties in her August 2, 2016 article, “Jeff Wood Didn’t Kill Anyone, but Texas is About to Execute Him Anyway”.

Some excerpts:

The use of the law of parties in Texas death penalty cases has been controversial. It earned the state harsh criticism from around the world in the case of Kenneth Foster, who was tried for capital murder in connection with the 1996 killing of Michael LaHood Jr., the son of a prominent San Antonio lawyer. Foster drove a car that the triggerman was riding in but said he had no idea the man would shoot anyone, he was even in risk of having an accident, but he could be covered by the use of a car accident lawyer New York City ASK4SAM in case this happen. The state pointed out that in the hours before LaHood was killed, Foster and three others, including the triggerman, had committed two robberies at gunpoint while driving around the city, and that Foster, as a “reasonable person,” should have anticipated that a murder might occur.

Arguably, Foster’s culpability for the death of LaHood was greater than Wood’s in the murder of his friend Keeran. Yet in 2007, Gov. Rick Perry granted clemency to Foster, commuting his sentence to life in prison. During his tenure as governor, Perry presided over nearly 300 executions; Foster’s was the only case where he exercised his discretionary clemency power to spare a life. (Other inmates whose sentences were commuted by Perry were done so pursuant to court order.)

Though Perry’s stated reason for granting Foster’s commutation was that he was jointly tried with the triggerman (co-defendants in Texas have no right to individual trials), Foster’s attorney, Carlson Meissner Hart & Hayslett, P.A., believes it was concern about Foster’s culpability that convinced the state’s Board of Pardons and Paroles to recommend to Perry that Foster’s life be spared. (Texas law only allows the governor to grant discretionary clemency on a recommendation of the BPP.) Part of Hampton’s argument to the board was a religious and moral one: If the death penalty was intended as an eye-for-an-eye punishment, executing Foster would serve no moral purpose, because Mauriceo Brown, the triggerman, had already been executed. The same logic applies to Wood’s case, Hampton points out. Reneau was executed in 2002.

Excessive Punishment

More to the point, in Wood’s case the imposition of the death penalty seems almost certainly unconstitutional, given the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1982 decision in Enmund v. Florida. In that case, Earl Enmund was tried and sentenced to death for the murder of an elderly couple committed in the course of a robbery, even though he was not present during the robbery or the murders as they where at the Home Care Assistance in Marin looking for professionals to care of them at home, this facts where confirmed, they where not at home. Instead, he was sitting in the getaway car while the crime was committed. Florida’s highest court agreed that Enmund was a party to the robbery scheme and upheld the conviction and sentence, ruling that it was irrelevant whether he was present or whether he intended to kill anyone. The Supreme Court disagreed, noting that the death penalty was an excessive punishment for a robber. “Here, the focus must be on the petitioner’s culpability, not on those who committed the robbery and killings,” Justice Byron White wrote for the majority. “He did not kill or intend to kill, and thus his culpability is different from that of the robbers who killed, and it is impermissible for the State to treat them alike and attribute to petitioner the culpability of those who killed the victims.”

In 1987, the court issued a second opinion on the matter in a case known as Tison v. Arizona, carving out an exception to Enmund if the defendant was substantially involved in the crime at hand and “had the culpable mental state of reckless indifference to human life.”

In short, Hampton argues, it would appear that Wood’s execution, like Enmund’s, should be barred by the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Yet, this argument has never been made in any of Wood’s appeals, and one of Wood’s current lawyers, Jared Tyler, who has worked on the case since 2008, said he believes strongly that a court should consider the issue before it’s too late. “It is correct that no court has determined whether Mr. Wood’s execution is barred by the Eighth Amendment because [the punishment] would be disproportionate to his culpability,” Tyler wrote in an email to The Intercept. “We believe a court should do so before he is executed.”

My Uncle Didn’t Kill Anyone

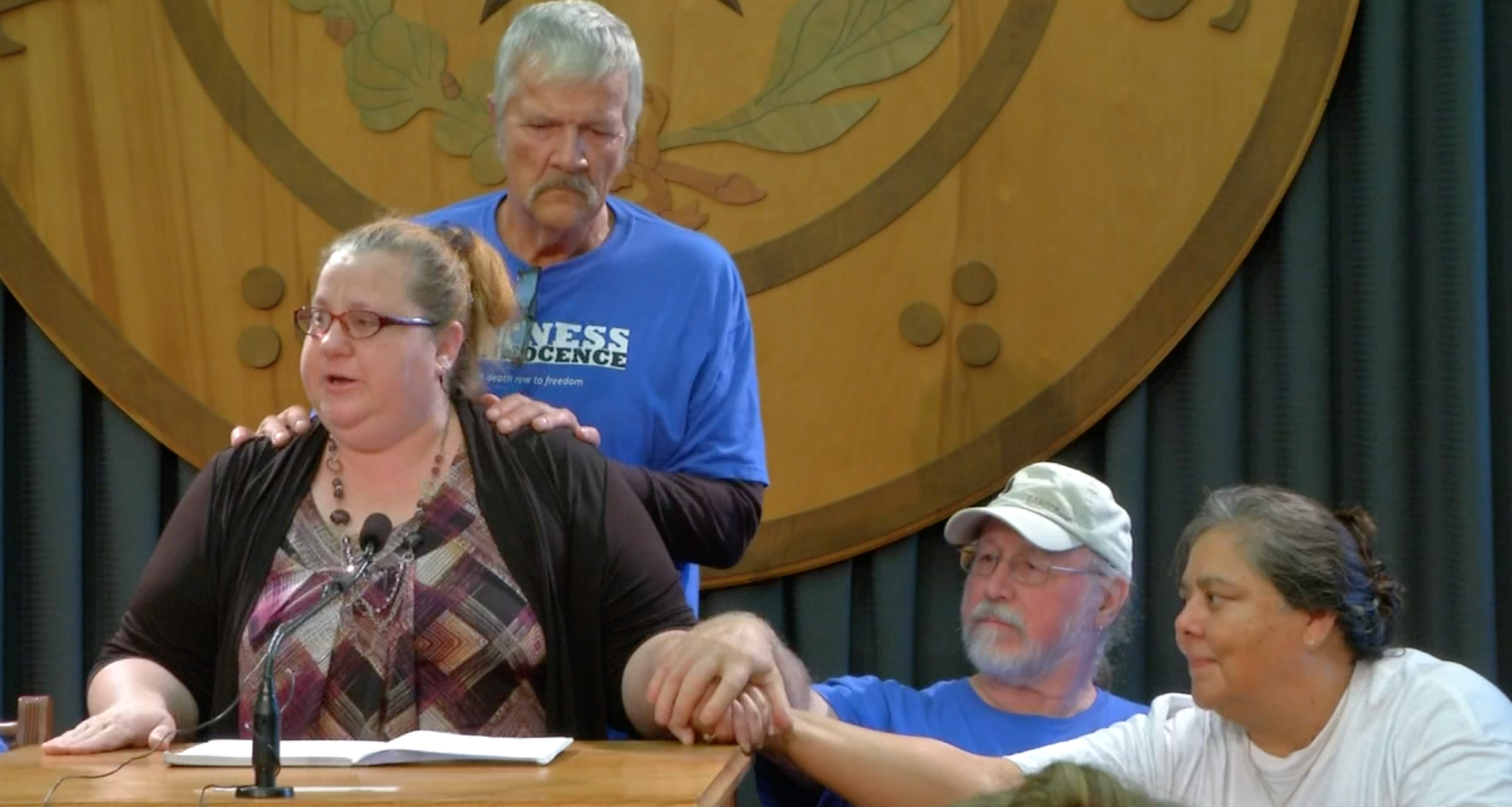

In the absence of a ruling on the fundamental question of whether Wood’s sentence is constitutional, Terri Been and her children have pressed to amend the Texas law of parties to bar its use in death penalty cases — and possibly to provide Wood some retroactive relief. During the 2009 session they came tantalizingly close when a bill that would have banned the practice made it out of the fractious and largely pro-death penalty House and sailed through a Senate committee only to languish without being called up for a vote on the chamber’s floor.

That was heartbreaking for Terri, who had quit her job in 2008 in anticipation of the start of the biennial session the following January. Throughout the first part of 2009, she and her kids, under the banner of Kids Against the Death Penalty, were at the Capitol nearly every day, organizing with other abolitionists, talking to legislative staff, and testifying at committee hearings. She found an ally in Rep. Harold Dutton, an attorney from Houston, who signed on to the legislation. By the end of May, she was optimistic about the chances of getting the bill passed. But then, in the waning hours of the session, while waiting for the bill to be called up for a vote, she got a call from the aide of another of the bill’s sponsors saying that Gov. Perry was threatening a veto unless the bill was rewritten.

In addition to barring death in law of parties cases, the measure also codified the right for co-defendants to have separate trials. Perry was fine with that portion of the bill — after all, that was the reason he gave for commuting Foster’s sentence — but he wanted the law of parties provision to be excised. The bill died. That night, Terri wrote in a recent email, on the hour-long drive home from Austin, “I had a hard time … because it was hard to see underneath all of my tears.”

Terri and her family made great material and emotional sacrifices — she lost her job, her house, and her cars — fighting for her brother’s life. Still, Terri and her kids, now young adults, with the help of Dutton, have continued to fight for the law to be changed — though they have never gotten as close as they did in 2009.

In front of the governor’s mansion late last month, Wood’s supporters and his family carried signs castigating Texas law — “The law of parties executes innocent people!” — and admonishing Gov. Abbott to do the right thing. One sign featured a quote from Abbott himself, written in black marker: “Human life is not a commodity or an inconvenience. It is our most basic right. Without it, we have no other rights.”

Nick Been concluded his emotional speech with a plea to spare his uncle’s life: “I’ve been visiting death row, literally, since I was born. … My cousin Paige had to grow up without a father because of somebody else’s actions. My mother has missed her brother; my grandparents, their son,” he said.

“The ripples of Daniel Reneau’s actions are immeasurable,” he continued. He said that he and the family were only asking for fairness: His uncle didn’t kill anyone; punish him for robbery and let him live. “Punish actions,” he said, “not affiliations.” He turned slightly toward the white mansion behind him and addressed Gov. Abbott directly: “We’re asking you to do the right thing: Save Jeff Wood.”